L&D Myth: Learning Styles (Visual, Auditory, Kinesthetic)

In the field of neuroscience, there are a number of "neuromyths" — a term that is now being used to describe misconceptions and inaccuracies about brain functioning. These are myths that pervade popular culture, education and business, including many L&D departments. According to research, there is no more widely believed and yet "thoroughly debunked" neuromyth then learning styles.

While learning styles is an umbrella term that can refer to a number of different categorisation models, the most well known is VAK: Visual, Auditory, Kinesthetic (Seeing, Hearing, Doing).

Important: The fact there exist people who believe passionately in the idea that they are, for example, a "visual learner" or an "auditory learner" is not in question as testing does indeed show repeated findings of individuals' stated "study preferences." What is in dispute, however, is the idea that having educators match the delivery of content to learners' stated preferences will improve learning. This central point of contention is what's known as the meshing (or matching) hypothesis. As noted by Pashler et al. (2008), the myth of learning styles is the myth that matching for preference necessarily leads to better performance:

"Most critically, the reality of these preferences does not demonstrate that assessing a student’s learning style would be helpful in providing effective instruction for that student. That is, a particular student’s having a particular preference does not, by itself, imply that optimal instruction for the student would need to take this preference into account. In brief, the existence of study preferences would not by itself suggest that buying and administering learning-styles tests would be a sensible use of educators’ limited time and money."

And the problem for proponents of learning styles is precisely that there is no credible scientific evidence to support this hypothesis, having now been reviewed and tested rigorously by several independent sets of researchers.

Quoted in the New York Times, Dr. Mark A. McDaniel, Professor of Psychology and the founding Co-Director of the Center for Integrative Research on Cognition, Learning, and Education, calls attention to the fact that “what you should see is visual learners do better on the visual than the verbal instruction, and verbal learners do better on the verbal than the visual instruction.” That doesn't happen. Instead, a leading expert in neuroscience and education, Paul Howard-Jones, in a separate New York Time article (How Brain Myths Could Hurt Kids) indicates that learning styles may actually be causing slight harm since research suggests that "some children appear to benefit more from receiving information in the style that they do not have preference for."

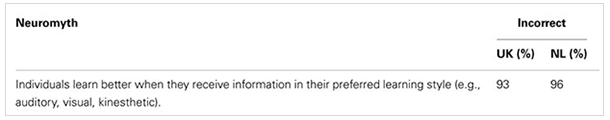

A 2012 survey of teachers in the UK and Netherlands (242 primary and secondary school) revealed that the learning styles meshing hypothesis was the #1 neuromyth for UK and Netherlands — believed by 93% and 96% respectively. Another study of 938 teachers in 5 countries, conducted by Paul Howard-Jones in 2014 of 938 teachers, placed the figure at 96%.

Source: Neuromyths in Education: Prevalence and Predictors of Misconceptions Among Teachers, Front. Psychol., 18 October 2012, Dekker, Lee, Howard-Jones, and Jolles. (UK = United Kingdom | NL = Netherlands.)

Yet the widespread acceptance of this teaching paradigm is in sharp contrast to the research that has been published in scientific journals and the growing campaign that is trying to raise awareness about these findings. 50 Great Myths of Popular Psychology (2009), Great Myths of the Brain (2014) and Urban Myths about Learning and Education (2015) are just three recent books that tackle the issue, while an array of scientific and mainstream articles have been written to set the record straight, including authors, scientists and journalists from the likes of Psychology Today, Popular Science, Scientific American, Washington Post, Wired, Inc. Magazine, Business Insider, The Guardian, Slate, BBC radio, and The Onion even has it's own satirical take: Parents Of Nasal Learners Demand Odor-Based Curriculum.

The OECD established the “Learning Sciences and Brain Research" project in 1999 as an authoritative resource dedicated to education on the subject of neuroscience and highlighting misinformation, which targets neuromyths such as learning styles.

The exact origin and spread of learning styles is beyond the scope of this article, however it is often associated with Howard Gardner's influential theory of multiple intelligences, who notes that people frequently credit him with inventing the term and some even believe the two concepts are the same thing. Gardner, keen to relieve the "pain" and "distraction" this misinterpretation has caused him, wrote a piece featured in the Washington Post (Howard Gardner: 'Multiple Intelligences’ Are Not ‘Learning Styles') in which he goes on to say, "If people want to talk about ‘an impulsive style’ or ‘a visual learner,’ that’s their prerogative. But they should recognise that these labels may be unhelpful, at best, and ill-conceived at worst."

COMPLEXITY AND EVIDENCE

While there has been a long list of researchers who have raised questions about the existence, identification, application and commercial exploitation of learning styles in education from a variety of different angles, there are two major reviews in particular that are often cited in the research literature, and thus worth singling out here.

The first is a 2004 review called "A Critical Analysis of Learning Styles and Pedagogy in post-16 learning: A systematic and critical review" by Coffield, Moseley, Hall, and Ecclestone. Commissioned by The Learning and Skills Research Centre, the four prominent cognitive psychologists identified 71 models of learning styles (yes, 71) with 13 being categorised as "major models" from 3,800 papers (yes, 3,800). Already, you can begin to appreciate the problem this amount of information poses to the average teacher or L&D professional, a point well highlighted in the report (which itself is over 200 pages):

"The enormous size of these literatures presents very particular problems for practitioners, policy-makers and researchers who are not specialists in this field. It is extremely unlikely that any of these groups will ever read the original papers and so they are dependent on reviews like this one, which have to discard the weakest papers, to summarise the large numbers of high-quality research papers, to simplify complex statistical arguments and to impose some order on a field which is marked by debate and constructive critique as well as by disunity, dissension and conceptual confusion. The principal tasks for the reviewers are to maintain academic rigour throughout the processes of selection, condensation, simplification and interpretation, while also writing in a style accessible to a broad audience. In these respects, the field of learning styles is similar to many other areas in the social sciences where both the measurement problems and the implications for practice are complex."

Another problem related to the communication of complex information required to help dispel neuromyths is that the latest, most up-to-date research is not necessarily easy to obtain, as explained by Dr. Paul Howard-Jones:

"In particular, an ongoing issue is that neuroscientific counter-evidence to dodgy brain claims are difficult to access for non-specialists. Often, crucial information appears in quite a complex form in specialist neuroscientific journals, and often behind an exorbitant paywall – for example, the Journal of Neuroscience charges $30 for one day of access to a single article. And yes, ironically it’s worth noting that the neuromyths paper is, frustratingly, also behind a paywall."

In the 2004 review, the 13 major instruments were analysed and matched against 4 "minimal criteria" (internal consistency, test-retest reliability, construct validity, and predictive validity), with "Only three of the 13 models – those of Allinson and Hayes, Apter and Vermunt – could be said to have come close to meeting these criteria." The researchers go on to say that "some of the best known and widely used instruments have such serious weaknesses (e.g., low reliability, poor validity and negligible impact on pedagogy) that we recommend that their use in research and in practice should be discontinued."

Despite the lack of scientific rigour by most publishers of learning styles inventories, the uptake and popularity of testing (particularly in the US and UK) is widespread and attributed to several reasons, including very small-scale research efforts conducted by test publishers (rather than independent researchers) that initially appeared to support the hypothesis, which is also addressed by the 2004 review:

"It is important to note that the field of learning styles research as a whole is characterised by a very large number of small-scale applications of particular models to small samples of students in specific contexts. This has proved especially problematic for our review of evidence of the impact of learning styles on teaching and learning, since there are very few robust studies which offer, for example, reliable and valid evidence and clear implications for practice based on empirical findings."

This point is further emphasised by cognitive psychologist Josh Cuevas:

"The strongest empirical studies published on the topic since 2009 have shown a consistent trend – they have found no effect of learning styles or the matching hypothesis (Allcock & Hulme, 2010; Choi, Lee, & Kang, 2009; Kappe, Boekholt, den Rooyen, & Van der Flier, 2009; Kozub, 2010; Martin, 2010; Sankey, Birch, & Gardiner, 2011; Zacharis, 2011). Two experimental studies did claim to find that elusive interaction effect, but one of those tested different behavioural outcomes rather than academic learning (Mahdjoubi & Akplotsyi, 2012) and the other used such a small sample size (N=39) and only a single 15-minute treatment (Hsieh, Jang, Hwang, & Chen, 2011) so the results would need to be replicated if we are to trust their credibility, particularly in light of so many other contradictory findings."

Probably the most often-cited and devastating critique of learning styles was the 2008 review, "Learning styles: Concepts and Evidence" by Pashler, McDaniel, Rohrer, and Bjork published in Psychological Science in the Public Interest, Volume 9, p. 106-119.

Their conclusion was as follows:

"Although the literature on learning styles is enormous, very few studies have even used an experimental methodology capable of testing the validity of learning styles applied to education. Moreover, of those that did use an appropriate method, several found results that flatly contradict the popular meshing hypothesis.

We conclude therefore, that at present, there is no adequate evidence base to justify incorporating learning-styles assessments into general educational practice. Thus, limited education resources would better be devoted to adopting other educational practices that have a strong evidence base, of which there are an increasing number. However, given the lack of methodologically sound studies of learning styles, it would be an error to conclude that all possible versions of learning styles have been tested and found wanting; many have simply not been tested at all."

Perhaps the best summation of the current scientific position on learning styles comes from John Hattie's Visible Learning and the Science of How We Learn (2013):

"There is no recognised evidence suggesting that knowing or diagnosing learning styles will help you to teach your students any better than not knowing their learning style."

Theo Winter

Client Services Manager, Writer & Researcher. Theo is one of the youngest professionals in the world to earn an accreditation in TTI Success Insight's suite of psychometric assessments. For more than a decade, he worked with hundreds of HR, L&D and OD professionals and consultants to improve engagement, performance and emotional intelligence of leaders and their teams. He authored the book "40 Must-Know Business Models for People Leaders."

We Would Like to Hear From You (0 Comments)